The number of homeless people in Ireland is increasing every year. According to the latest figures released by the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, including 3,752 children, 10,448 people are currently homeless in the state.

In 2014, when the homeless crisis worsened in different cities across the state, many people were evacuated to emergency shelters.

What is shocking is that there are now more than 18,000 people in the country who have been on social housing waiting list, seeking State-supported homes for more than seven years now.

New solutions to Ireland’s housing crisis are needed from private housing projects to mortgage-to-rent schemes, and from co-operative housing to cost-rental homes.

The Irish national daily newspaper, Irish Examiner examined two innovative models that were being carried out in Ireland.

One is a first-of-its-kind co-housing initiative, Common Ground Co-Housing in Wicklow, other is an affordable housing co-operative, developed by cohousing alliance Ó Cualann, which has already built 49 homes in Dublin.

The Wicklow project is a repaid shared loan and individuals hold shares as opposed to deeds. While the other is an owner-occupied scheme.

None of the models are social housing, but both are relatively inexpensive compared with existing market prices.

A relatively inexpensive model

HUGH Brennan is CEO of Ó Cualann, an authorised residential entity that has already housed 49 families in Dublin under its affordable cooperative model of housing. It has several other projects currently under way in Ireland, including in Cork.

The organisation was officially set up in 2015, and construction on their first site in Ballymun began in 2017.

“We are now halfway through our second project, which is also in Ballymum. There are 37 homes now and a further 12 are coming in June 2020. Then we have 25 in Callan, Co Kilkenny, 20 in Ardmore, Co Waterford and 17 in Knocknaheeney, Co Cork,” Mr Brennan said.

Nationally, Ó Cualann will be working on a total of 5,000 of these homes, according to their strategic plan.

Mr Brennan explained how the cohousing alliance worked, stating that it was like any other private development, but the cost of your home is based on the build cost. Therefore, it comes down to getting an affordable site to build on in the first place.

“It’s not social housing at all, it’s funded by the members — it works like any other private development. It’s all based on cost, we calculate what it costs to build, take all fees into account and add on 5%.

“A three-bed, A2 rated, 100sq m home in Ballymum costs €219,000. Outside of Ó Cualann and on the private market a similar house currently costs €360,000,” said Mr Brennan.

Your mortgage is either with one of the banks or Rebuilding Ireland.

With 1,500 people currently on the housing body’s waiting list, there are criteria that prospective homeowners must meet under their affordable model.

“There are eligibility criteria. We get land at a reduced rate from say a local authority, and between Ó Cualann and the council — the criteria of members is agreed. We give first preference to anyone who lives in the area, who lives in a council house and will surrender that and buy one of ours,” said Mr Brennan.

“Then there are income limits, you can’t have earned more than €59,000 as an individual or €79,000 as a household in previous tax year, but that changes by area.

“Once you’ve already signed up, we then allocate houses on a first-come first-served basis. We have 1,500 people on our waiting list and when a new scheme comes on board we contact people,” he added.

Prospective homeowners must also show that they can get approved for a mortgage and that they have a deposit for their property.

While their housing model has similarities to any other private development, it is markedly different due to its affordability factor. However, in order to scale and replicate the model, affordable land all around Ireland must be made available.

“In order to make it affordable, we need to get land at a discounted rate, be that from local authorities, religious orders or State agencies. The crux is to get an affordable piece of land,” said Mr Brennan.

Ó Cualann, with completed sites in Dublin and projects underway in three other counties, said they can replicate their model “everywhere”, but that a “blockage” exists.

“We can do it everywhere, the only blockage is State agencies making land available. [In Ireland], we have enough land to make this land available. It doesn’t even cost the State anything, they’ll still be getting a cheque and there is a huge positive knock-on effect for a local community,” said Mr Brennan.

“People who have been renting before they move in, when they move to a mortgage they’re paying €600 to €700 less than what they were paying in rent. Research has shown that either 40% of that gets saved or goes to a new car or holiday, but the other 60% is spent on local childcare and in local shops and cafés.”

It is estimated that in Ballymum alone, where there are sites available for 2,000 homes, the general income of the area would be increased by €13m by assisting people to move from renting a property to paying a mortgage on one.

Mr Brennan believes that this “blockage” about making sites available for purchase to housing bodies, as opposed to private developers, stems from the State seeing their land as a “commodity to be sold to the highest bidder” instead of as a resource.

“If they sell to a developer, even if they make a load of money, it’s only a pittance compared to what they’d get from investing in community,” he said.

Environment friendly

LILAC (low-impact living and affordable community) is a co-housing community of 20 eco-build households in Leeds.

The homes and land are managed by residents through a mutual home ownership society (MHOS) — a financial and legal model that ensures affordability.

There are five blocks of this housing in Leeds, with some blocks consisting of six smaller homes and others comprised of two larger homes. The blocks all face each other and into shared gardens.

On the perimeter of the site there is a shared bike shed, with two recycling centres, and two areas to park several cars. There is also a large play area and a productive garden within the Leeds co-housing community.

The building and homes are extremely environmentally friendly.

The homes on the site were built in conjunction with ModCell — a company that has developed a low- carbon method of construction, using timber panel walls insulated with straw bales. This method of construction significantly reduced the CO2 emitted during the Leeds building process.

Members were involved in the building process after the structural timber was assembled, and were able to assist in adding the straw bales.

There are solar panels in use in the development too. The insulating materials and design of the buildings store solar heat in the winter and reject solar heat in the summer, therefore reducing the need to have external heating energy.

The houses also have solar thermal for space and hot water heating.

Each home has what is known as a “mechanical ventilation heat recovery system” (MVHR) which enables the indoor air quality to remain high, without having to open the windows.

The low-impact aspect of the co- housing community extends beyond the buildings. The people living there do car-sharing and pool things such as tools and other equipment.

Growing food in their allotments means they eat as locally as possible.

In terms of the legal parameters in Leeds, each member has a lease, which gives them democratic control of the housing community.

Members pay an equity share to the co-operative and retain equity in the scheme. Once deductions have been taken for maintenance and insurance, these payments pay the mortgage.

The payment that leaseholders pay each month is set at around 35% of their net income.

There are also processes in place when it comes to changes, such as members leaving or incomes fluctuating. As members leave, existing members can buy more equity shares, and as people’s income levels change, their equity share commitments can also change.

However, there is one rule regarding a three-year investment in the community.

If someone leaves sooner than three years, they will not be entitled to increases in the value of their equity shares.

To ensure the sustainability of the project, the company keeps a set percentage of any increase in equity.

Lilac started in 2006 with a group of five people who were already living in Leeds.

These five people were interested in the idea of building their own homes.

After three years of research and planning, with help from new members, Lilac Mutual Home Ownership Society Ltd (MHOS) was registered as a co-operative society.

Building then commenced in 2012, after development capital had been raised and a builder and an architect procured. The first wave of residents moved in in May 2013.

Funding for projects in Ireland, particularly Common Ground Co-Housing, will use the same legal structure and funding model as Lilac, using the mutual home ownership society model.

MHOS enables a group of people to join together to buy or build homes that they could not otherwise afford to purchase.

As with traditional home ownership, households’ investment comprises of initial capital, a deposit, and then a mortgage for the remainder of the cost.

In the case of MHOS, a group of households takes out a collective mortgage and each household is responsible for paying a share of it.

Then, in return for their investment, members get equity shares in the society and the use of one of the homes.

With MHOS, costs can be spread across the group according to a household’s ability to pay.

For example, more affluent households can buy more equity shares than the value of their home, making other homes in the scheme more affordable for households on modest incomes.

When it comes to exiting the co-housing community, a householder can leave and sell their equity shares, releasing the capital to buy a home elsewhere.

The whole concept is designed to make home ownership affordable and accessible and to build a community.

It also allows residents to have greater control over their housing than if they were renting from a private landlord.

Monthly payments cover a maintenance charge and secure equity share units in the society, which uses these funds to repay the development loan.

Develop common housing grounds

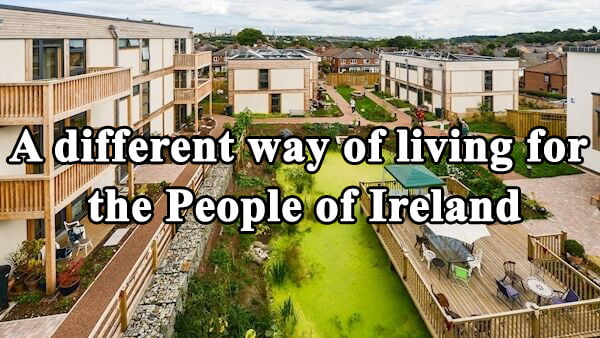

Common Ground Co-Housing in Co Wicklow is a group of 33 individuals that have come together to buy a site for their individual homes, but under one common loan.

If successful, it will be the first development of its kind in the history of the State.

The group is currently forming a legal entity and looking for a two-acre site in Greystones. It is hoping to replicate a model used in Leeds, UK, called Lilac, which stands for low-impact living and affordable community.

There are 20 homes on the development in Leeds, and that group used a special legal structure and funding model, called MHOS — mutual home ownership society.

MHOS allows groups of people to club together to buy or build homes that they might not otherwise be able to afford.

The society takes out a collective mortgage and each home is responsible for paying a share of it.

In return for their investment, members get equity shares in the society and the use of one of the homes.

This has been successfully achieved in Leeds for 20 homes, and Common Ground Co-Housing in Co Wicklow is in the process of replicating it for 25 households, with a total community of about 53 people.

“In our 25 households we have a mechanical engineer, a nurse, a midwife, teachers, an osteopath, a landscape gardener, and a psychologist,” said Deb Davis a founding member of Common Ground Co-Housing. “We have from a one-year-old to someone in their late 60s.”

The idea started in 2018 after a public meeting and has grown since then.

“We put it out to the members of Common Ground Bray [a community group with 400 members], and 60 people came to our talk. That was in June of 2018,” she said.

“We outlined our stringent application process, including who we were, what we were, and time commitments and financial commitments.

“We got 37 people who were all prepared to put €1,000 into a pot as a commitment to say ‘Yes, I’m interested in this’. There was no guarantee that anything was going to be coming out of it.

“It was to go towards expenses to bring in professionals where we didn’t have the skillset ourselves,” said Ms Davis.

We have an architect in the group, but lawyers to help us set up our company — we didn’t have that level of skill.

That initial number of 37 people now stands at 33.

On their prospective site, the group is hoping to have one common house for shared use, and 25 individual homes for each of the households.

“There are individual houses. We all have our own front door. So one of the most important things to point out is the difference between co-housing and co- living. People are getting confused. We are not co-living, we are co-housing.

“It’s a little enclave of houses like any housing estate, only it’s an intentional community, so we’ve chosen our neighbours and we get to make decisions together of how we want to plant the place — it’ll be based on permaculture. It’s about people flourishing,” explained Ms Davis.

“The common house is a space where meals are shared as often as people want. It’s an area that can be used during the week for classes — so yoga classes.

“It would offer affordable classes for the wider community. It would be a community house for socialising,” she added.

THE funding model, MHOS (mutual home ownership society), which the group is planning to use has never been tried in Ireland before. However, it has been used in the 20-home community in Leeds.

The Irish group is putting the legal parameters in place to set up its own MHOS structure.

Once this has been done successfully, Common Ground Co-Housing plans to openly share its model with other interested groups around the country.

The Irish group will hold the land in a “community land trust” that can never be sold. The homes are then built on this land.

“We will own shares in the whole co-operative. Some people will be in one-beds, some people will be in two-beds,” said Ms Davis.

“Let’s say its 25 dwellings all with their own front door, we will own, for the sake of simplicity, a 25th of the shares.

“If someone wants to sell and leave the co-housing community, they sell their shares, not their home.”

The shares are index-linked to the national wage. They are not linked to what property prices are doing in the market at any given time.

It is estimated that a home would be ready from within two years of turning the first sod, Ms Davis said.

She said that their plan is about creating an alternative to what is already out there on the private market, or lacking in the general housing stock.

“You get to choose: Do what they’re doing over here with the results they’re getting, or have the courage to try something new and get different results,” said Ms Davis.

Possible alternatives

Solution 1: Cost-rental

The cost-rental is affordable, high-quality rental accommodation, provided by the State or local authorities, or in conjunction with an approved housing body.

The rent is used to cover the cost of constructing the accommodation over the life of a long-term building loan.

The premise is that you build homes and the rent is affordable. It works out 20% to 30% lower than the private for-profit rental market.

The cost of rent reflects the cost of providing and maintaining the homes. The affordability is made possible because the developer’s profit is taken out of the equation.

Cost-rental is seen as the “positive disruptor” in the private rental market. It provides homes for people who don’t qualify for social housing, but also cannot afford to rent.

It is already being rolled out in Ireland. The two housing developments, one in Sandyford and the other in Inchicore will together deliver nearly 400 cost-rental homes. Two approved housing bodies, Túath and Respond, are involved in developing one of them.

The Department of Housing has said it will use what is learned from these two projects to see if the concept can be rolled out nationwide.

Solution 2: Switch mortgage to rent schemes

This concept is for people who are in long-term mortgage arrears and who will never be in a position to repay their mortgage, and interest on it, as it currently stands.

It involves people surrendering their home but then being able to live in it for a 25-year period like social housing.

The concept was introduced by the Government in their housing and homeless action plan — Rebuilding Ireland.

The iCare Housing group, a charity and approved housing body, operates under the scheme — iCare converts people’s mortgage on a property (if they qualify) to them renting the same property. They surrender the house to the bank or vulture fund, if their original lender has sold their bad loan.

Then iCare buys the house from the bank. The householder has their debt written off and they then become social housing tenants of iCare.

By last Christmas, iCare had purchased its first 19 houses, keeping more than 50 people in their homes.

The group helps people who are in houses but with mortgage arrears and who are not eligible for social housing (an annual household income of below approximately €35,000).

The scheme sees banks and debtors working together for a solution that does not involve the courtroom.

Solution 3: Charities with innovative projects

There are approximately 245,460 vacant dwellings in Ireland, according to Census 2016. Bringing these properties back into use is one way to tackle the housing crisis.

The Peter McVerry Trust (PMcVT) has focused heavily on utilising “long-term vacant homes”.

To do so, PMcVT buys long-term vacant units or takes them on a social lease and then turns them into social housing.

The trust has dozens of projects all over Ireland, having gone from just three or four social housing units in 2008.

Some projects include nine apartments in Westmeath from shops that were built as part of an apartment complex but were then left vacant. This is an example of former retail units being turned them into apartments.

The trust also purchased two derelict buildings in Co Kildare to return to residential use.

Another project of theirs is located near Dublin Castle, where there was a partially-finished development that was part of a portfolio that needed to sold off quickly.

This project provided 13 new social homes to homeless people on the public housing waiting list.

The trust has also regenerated 18 social housing units on Dublin’s Townsend St belonging to Dublin City Council, and last April, it provided 11 new social housing units in Drogheda after renovating more spaces over shops.

In all of these cases, the properties are treated as social housing, so tenants pay a rent.

Solution 4: A mixed-finance platform

In order to provide housing, it is not just sites and existing properties that are needed but funding too. There has also been some creativity happening in this area when it comes to solving the Irish housing crisis.

Focus Ireland, for example, teamed up with Premier/Setanta Sports Group, which is pledging €1m in equity to deliver 40 homes through a specific mixed-funding model.

Mixed-funding means social homes are financed by some State capital and some privately-raised money.

“How this works is that €25,000 is the average 10% equity deposit Focus Ireland has to have in place to leverage the finance required to buy a typical 2+ bedroom family unit,” according to Focus Ireland.

“Once Focus Ireland has the 10% equity deposit in place this enables the charity to borrow 70% from the Housing Finance Agency and the other 20% required for the purchase of the home is funded through the Dublin City Council CALF scheme.

“Based on this mix, and of course subject to market and lending fluctuations — €1m would mean that Focus Ireland should be able to secure 40 units.”

Mixed funding was introduced here in 1984. The housing associations would have received 90% to 95% State capital and they would have had to raise between 5% and 10%. Mixed-funding was used to a small degree.

However, since 2010, the mixed-funding scheme changed, where housing associations receive 30% State capital and have to raise 70% private loans or other finance. The mixed-funding model is typical in other EU countries.

Using the mixed-funding model, social housing is less susceptible to the boom and bust cycle, as it is not reliant on State capital expenditure.

Another method of funding housing is by involving major businesses with large workforces in Ireland.

This is not a new concept in Ireland. Guinness, Bórd na Móna, Philips in the Netherlands and Cadburys in the UK, either directly or in joint partnerships with non-profit housing groups, have played a major role in social and affordable housing.

Comments are closed.